Hysteria

The Historical Relevance

Definition

a psychological disorder (not now regarded as a single definite condition) whose symptoms include conversion of psychological stress into physical symptoms, selective amnesia, shallow volatile emotions, and overdramatic or attention-seeking behavior. The term has a controversial history as it was formerly regarded as a disease specific to women.

Female Hysteria

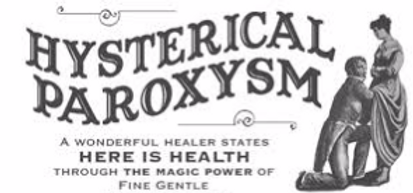

Female hysteria is the now-defunct term used to diagnose a woman who suffered from any variety of ailments. The prefix hyster comes from Greek for uterus. Symptoms included anything from fainting to erotic fantasies, to a loss of appetite, to “a tendency to cause trouble.” Basically, anything that couldn’t be directly attributed to something else fell under the “female hysteria” umbrella. A Roman physician named Galen theorized that this hysteria, this movement of the womb, was caused by sexual deprivation. Professionals thought women who were married had an easy fix – simply enlisting their husbands to help them out. However, for unmarried women, widows, and those who were devoted to the church, things weren’t so easy. By the 1800s, hysteria was widely accepted as the most common disease amongst women and one that doctors found themselves treating with increasing frequency. In fact, a French physician named Pierre Briquet made the bold claim that at least a quarter of all women in the Victorian era suffered from “hysteroneurasthenic disorders.”

Male Hysteria

Why was it so rarely diagnosed in men?

It’s not that the behavior didn’t exist. It did exist. It was rampant. Men were as prone to nervous breakdowns as women were. It was not diagnosed for social and political reasons. Men were believed to be more sane, more motivated by reason, more in control of themselves emotionally. If one was to diagnose honestly, that would have pretty quickly called into the question the difference between the sexes and the idea that men were more self-possessed than their "fragile", "dependent" female counterparts. Ultimately it comes down to patriarchy and power. However, for a brief time, in Georgian England, it was almost fashionable to be a hysterical man. Why? In 18th-century England and Scotland, it was acceptable to acknowledge these symptoms in men and call them “nervous.” The label was applied, and self-applied, to men who were upper-middle or upper class, or aspired to be. They interpreted these symptoms not as a sign of weakness or unmanliness but as a sign that they had a refined, civilized, superior sensibility. If the weather depresses you, if you get emotionally involved in reading a Shakespeare play, if you tire out easily, it’s not because you’re unmanly, it’s because you have a particularly sophisticated nervous system that your working-class counterparts do not. And if you can convince other people in society of this, then doesn’t it mean you’re better suited to govern the state wisely?